HIV Cure & Immunotherapies Approaches: a brief overview

Written by Devan Nambiar, MSc, Branka Vulesevic, PhD, and Cecilia Costiniuk, MD MSc

Medical Review by Dr. Jonathan Angel and Dr. Carla Coffin, MD

About this resource

This document, produced by the CTN+’s Cure and Immunotherapies Think Tank in response to requests by community members, is intended for people living with HIV, front-line staff, and community members seeking information about the immune system and the potential HIV cure and immunotherapy strategies currently under investigation. Before outlining these main approaches, a brief overview of the immune system — and HIV’s impact on the immune system — is provided. The various phases of clinical trials are also outlined.

This document has undergone review by community members for clarity and accessibility. If you have suggestions or questions, please contact us at info@ctnplus.ca.

Overview of the immune system

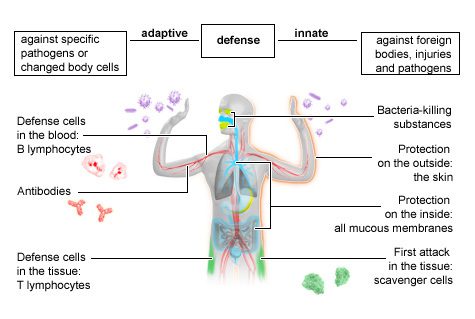

The immune system consists of cells and organs which protect you from various pathogens or “germs,” such as bacteria, virus, fungi, and parasites, that can cause infection and disease. The immune system also gets rid of dead and potentially harmful cells, such as pre-cancerous cells.

First line of defence

Innate immunity is the first line of defence against invaders. It is called “innate” since it is present at birth and does not require exposure to a specific pathogen to be activated. The innate immune system is made of physical barriers (skin and mucous membranes that block the movement of foreign cells); enzymes (proteins that speed up chemical reactions); phagocytes (cells that surround and kill invaders, ingest foreign material, and remove dead cells); cell receptors (that sense microorganisms or germs and signal a defensive response); and cytokines and chemokines (proteins which facilitate communication between cells with a range of both stimulating and inhibiting functions).

The innate immune system does not require previous exposure to a pathogen to know how to respond. When innate immunity does not work sufficiently to kill the pathogen, the adaptive immune system kicks in.

also known as Acquired immunity

Adaptive immunity, also called acquired immunity, takes longer than innate immunity to recognize pathogens but it develops responses specific to each pathogen it encounters. The adaptive immune system then remembers this response for the next time it meets the pathogen so it can quickly and effectively respond and allow the body to heal quickly.

You may also hear the terms cellular immunity and humoral immunity. Cellular immunity refers to adaptive immune responses using immune cells like T cells and B cells. Humoral immunity refers to immune responses related to antibodies. During most infections, these two branches of the adaptive immune system work together to fight and protect against pathogens. You can learn more about some of the different types of immune cells involved in these cascades in Cells of the Adaptive Immune System below.

Neutrophils

These cells make up between 50% to 80% of all white blood cells. They act as the immune system’s first line of defense. Neutrophils capture and destroy the invading pathogens by setting “traps” and ingesting them. Neutrophils make important contributions to the recruitment, activation and programming of other immune cells. They also secrete various pro-inflammatory and immunomodulatory cytokines and chemokines which enhance recruitment and functions of other cells. Neutrophils also engage in interactions with a range of immune and non-immune cells and contribute to the resolution of inflammation and promotion of healing by clearing debris and releasing growth factors which stimulate repair mechanisms.

Dendritic Cells and Macrophages

Dendritic cells are a type of cell which presents antigen to the immune system and are distributed throughout the body. In Greek, macrophage means “big eater.” As the name suggests, these cells act as scavengers, engulfing or “eating” pathogens. These cells are located at mucosal entry points, such as the mouth, vagina, and rectum, and within different organs, including the gut, lungs, liver, and brain. These cells also capture and carry invaders to the lymph organs. Once engulfed, a small piece of the foreign invader — known as an antigen — is displayed on the macrophage’s surface. The adaptive immune system then uses this information to program specific immune cells and produce antibodies to mount a response. Macrophages also produce cytokines, which are chemical messengers that instruct other immune cells to rise to action.

T cells

After pathogens are destroyed and displayed on the surface of macrophages, they can be recognized by CD4 T cells, also known ashelper T cells. When CD4 cells see the antigens, they communicate with other T cells, such as killer T cells and macrophages, by releasing many different cytokines. Killer T cells, also called cytotoxic T cells, directly attack and destroy cells infected by pathogens, as well as other abnormal or pre-cancerous cells. Once the foreign invader has been killed, suppressor T cells tell the immune system to stop fighting. Both killer T cells and suppressor T cells are types of CD8 T cells.

b cells

B cells are also activated by CD4 cells. When a B cell recognizes an antigen, it produces specific proteins called antibodies. Antibodies attach themselves to antigens to neutralize or paralyze the antigen. It usually takes a few weeks to make an antibody when a pathogen is first encountered. However, if the immune system is exposed again in the future to the same pathogen, specialized B cells, called memory B cells, remember the pathogen and jump into action immediately to neutralize the pathogen. This mechanism of previous exposure is the basis for most vaccinations used today.

Together, the innate and humoral components of the immune system work together and set off a complex cascade of immune functions as shown in the figure below.

Fig. 1. In brief. The innate and adaptive immune system. 2023. National Library of Medicine.

HIV & the Immune System

First line of defence

HIV is a type of virus called a retrovirus, meaning its genetic material, which is RNA, is converted into DNA when it infects a host cell. This occurs through the activity of an enzyme called reverse transcriptase. This HIV DNA is then inserted (integrated) into the DNA of the host cell. Within hours of entering the body, HIV attacks cells of the immune system, and especially CD4 cells. HIV turns these CD4 cells into factories that make more copies of the virus. The body responds normally to this new infection by stimulating B cells to produce antibodies to HIV. However, these antibodies do not get rid of HIV — like they do for many other infections.

As HIV reproduces, it damages or kills the CD4 cells it has infected. Over time, both the number and type of CD4 cells are reduced. Without enough CD4 cells, the immune system struggles to mount an adequate response. HIV can also infect macrophages and other immune cells and impair their function. When the immune response is not properly activated and organized, people become at risk for opportunistic infections and cancers that usually do not harm people with intact immune systems. As it replicates and travels throughout the body, HIV forms “reservoirs.”

also known as Acquired immunity

An HIV reservoir refers to a collection of inactive, “resting,” or latent HIV-infected CD4 T cells. These reservoirs can be found throughout the body, including in the gut, lymphoid tissue, blood, brain, genital tract, and bone marrow. It is unclear when reservoirs are established, but recent research suggests that it could be as early as 24 hours after initial infection. The HIV-infected cells in these reservoirs continue to copy themselves, expanding the reservoir while hiding from the immune system and antiretroviral drugs.

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) works by stopping HIV from making copies of itself and therefore stops it from infecting other CD4 cells. When ART is started soon following infection, it doesn’t prevent the formation of reservoirs, but can minimize their size. Furthermore, since CD4 cells are key players in the immune response, early ART initiation can give the body a chance to replenish its CD4 cells, thereby protecting against other infections. However, ART needs to be taken life-long. If ART is stopped, the HIV hiding in the reservoirs will wake up and start replicating, causing HIV to rebound in the blood within about two weeks of stopping ART. The need for lifelong ART is one of the major reasons why people are interested in developing a cure for HIV. Elimination of HIV from the body (complete cure) will require not only that HIV be eliminated from the bloodstream, but also from the viral reservoirs.

Overview of HIV Cure Research

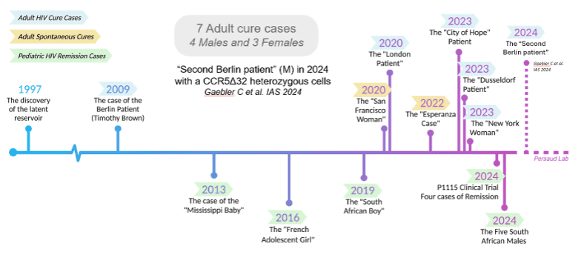

Since the “The Berlin Patient” in 2009, the first person in the world to be cured of HIV, there have been seven people cured of HIV. After undergoing radiation treatment for cancer, each of these people received a stem-cell transplant from donors who had natural immunity to HIV (see Gene Therapies below).

As of 2024, fifteen years later, three people have been cured of HIV after stem cell transplants replaced all the cells of their immune systems. Stem cell transplants were performed with the primary goal of treating blood cancers and as a life saving measure. This procedure is risky, and 5–10% of people receiving a stem cell transplant do not survive, meaning that it is not a viable option for curing HIV in people without cancer. Another three similar cases have been reported, but it is too early to know if HIV has been completely cleared in these people. Furthermore, several cases of HIV control after stopping antiretroviral treatment have been reported. In these people, HIV may still be present at extremely low levels but it is being controlled by their immune systems.

The figure below shows the timeline of these remission and cure milestones, presented at the AIDS 2024 conference. The Berlin Patient in 2009 prompted major global research efforts to find a cure that would be safe, effective, and widely available. The information presented below is not an exhaustive list of all the cure research but highlights many of the HIV cure research approaches currently under evaluation in clinical trials.

Fig.2. IAS. 2024. AIDS 2024 Knowledge Toolkit. Highlights of the 25th International AIDS Conference.

HIV cure-related research can be broadly categorized into one of two categories, based on the overall goal of the strategy:

Eradication or complete elimination

This type of cure refers to getting rid of all HIV from all locations in the body. This also called a “complete cure” or “sterilizing cure.”

Durable antiretroviral-free control

This refers to a cure that results in HIV still being in the body, but it is not active and cannot affect one’s health or be passed to other people. This is also called a “functional cure.“ Most researchers believe this approach is more likely to be achieved than a complete cure. Sometimes people refer to this as HIV remission. Remission means that HIV is not active in the body; there is no guarantee of lifelong control of the virus, and it suggests the need for continued monitoring to ensure that levels of the virus do not increase again many years later.

HIV Cure Strategies

Below are several categories of HIV cure trials, along with brief descriptions. Each approach has advantages and challenges.

Optional Subheading

This approach is also called “kick and kill”. The resting cells containing latent HIV are “kicked” into action and then the newly activated cells are “killed” or cleared. Once the cells and the virus become active, there is increased expression of viral proteins that are recognized and attacked by the immune system. The substances that provide the kick are called latency reversing agents (LRAs).At the same time as HIV-harbouring cells become activated, ART prevents uninfected cells from becoming infected with newly active virus that has been kicked into action. In order to clear the activated cells, LRAs need to be combined with therapies that stimulate the immune system, like Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists, immune checkpoint inhibitors, therapeutic vaccines, and broadly neutralizing antibodies. These immune systems stimulators are discussed below (see Immune-Based Approaches below)

Some LRAs are already used in humans for other conditions (for example, cancer treatment) and research involving their use in people with HIV have been conducted.

In contrast to “shock and kill”, this approach aims to permanently silence latent HIV using latency promoting agents (LPAs), “blocking” transcription in the cell’s lifecycle. The agents used would be specific to HIV (for example, by targeting a gene specific to HIV). Over time this would trap the virus in reservoir cells so it cannot escape. ART would no longer be required.

At this stage, this approach is theoretical. There are currently no LPA therapies approved by the US Food and Drug administration nor Health Canada for use in humans and no clinical trials.

Genes are the most basic pieces of hereditary information and carry DNA in all living things, including humans and viruses. Researchers believe that treatments that cause the genes to change their behaviour can be used as a way to cure HIV. Three broad approaches to gene therapy exist:

knocking out genes in HIV that allow it to enter and infect immune cells

The genes that provide the instructions for HIV’s ability to enter cells are deleted or “knocked out.” Although HIV remains in the body, it is unable to infect cells.

knocking in genes to our immune cells that make them resistant to HIV

Some people are born with protective genes. These people are protected because they don’t produce a receptor called CCR5 on the outside of their immune cells that HIV needs to enter and infect the cells. The Berlin Patient received a stem cell transplant from a donor with a genetic mutation that means his CD4 T cells do not express CCR5, making them resistant to HIV infection.

cutting out the genetic pieces of HIV that have become integrated into the DNA of infected immune cells

This approach uses technologies (e.g., CRISPR) that latch very precisely onto the HIV genes that have integrated into human DNA and cut them out, replacing them with shorter regions of inactive DNA, without harming the cell. This approach has been used successfully in a lab setting where T-cells resistant to HIV were produced.

These approaches work by enhancing the immune system’s ability to clear infected cells and achieve a cure. These approaches are not used by themselves, but are combined with other approaches. Three main approaches are being investigated:

Broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs)

Like regular antibodies, bNAbs recognize antigens displayed on surface of macrophages and then seek out and neutralize other antigens throughout the body. However, while regular antibodies can only match up with and destroy one specific antigen, bNAbs can recognize and target many different antigens. In this way, bNABs can recognize several strains of HIV, making them more effective at catching and destroying the virus throughout the body.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy

CAR T therapy is approved for use in certain types of leukemia, and it is being studied in other kinds of cancers. For people living with HIV, this approach can be used to reprogram T cells to better identify and eliminate cells containing HIV. Clinical trials exploring CAR T cells as an approach to cure HIV are underway in humans.

Most likely, we will need a combination of approaches to achieve ongoing control of HIV without HIV drugs. Scientists are investigating safe ways to combine different HIV cure research approaches. Various combination strategies are currently under investigation in clinical trials. For example, in one proof-of-concept study aimed at inducing HIV remission, twenty participants are undergoing five stages of intervention 1) administration of a DNA vaccine, an MVA Vaccine Boost, a TLR9 agonist (lefitolimod), two different bNAbs (which target different sites important to the HIV life cycle). Participants will then be followed up after stopping ART. This study is aimed to finish by December 2025.

The Treatment Action Group (TAG) in the US published an online list of HIV cure-related clinical trials and observational studies (studies which do not involve an intervention) based on clinical trial registries. It can be accessed here.

Phases of HIV Clinical Trials Research

A clinical trial is a research study in which people volunteer to help researchers find answers to questions related to a given health or medical issue. HIV clinical trial research studies were crucial to developing antiretrovirals currently used in HIV therapy. Often the research starts in a laboratory within test tubes and cells in culture. This is referred to as “in vitro” or pre-clinical research. Promising in vitro studies then typically progress to studies in animals, referred to as “in vivo” research.

Typically, studies are conducted in animals using models intended to mimic what is expected to happen in humans, before the research is approved for studies in humans. If the results are successful, the research may proceed to a Phase 1 clinical trial. Most of the research on HIV cure and immunotherapy strategies is in these earliest phases. Cure research aims to identify strategies that show promise and may eventually lead to broadly effective cure approaches.

Phase 1 Research focuses on the safety and tolerability of the drug or intervention. Different doses are used to find a safe dose and to assess side effects. The number of participants is usually around 20–100 people. The study can last a few days, or week, or a month. If the intervention is found to be safe enough to proceed, the research can move on to Phase 2.

Optional Subheading

Phase 2 Research focuses on the effectiveness of the intervention. The research aims to determine whether the treatment works as well as ongoing safety assessment in a few hundred participants, and for a longer duration than Phase 1 (usually 6–12 months). Phase 2 studies sometimes also examine different doses to identify the dose that works the best. If the results in Phase 2 are successful, it goes to Phase 3.

Phase 3 Research aims to confirm the effectiveness and safety of the interventionstudied in larger groups of participants (often 1,000–3,000) for longer periods of time (2–3 years). More safety data is collected from the participants. If results are promising and safe in a Phase 3 clinical trial, the data can be submitted to a health authority (e.g., Health Canada) to seek approval for the therapy.

Phase 4 Research is commonly known as post-marketing studies. After a drug or vaccine has been approved and licensed in Canada, Phase 4 studies continue to monitor long-term effects and safety of the intervention.

Clinical trials involving people with HIV go through Phases 1, 2, and 3 and can be tested in one research center or across many centers and countries. All HIV research studies have inclusion and exclusion criteria for who can be in the study and have their study protocols approved by an Ethics Research Board.

As with other types of clinical trials, research in HIV has strict ethical and informed consent guidelines. If you are considering participating in a trial, or just to learn more, use the search feature on ClinicalTrials.gov to find HIV studies looking for volunteer participants. Some HIV and AIDS clinical trials enroll only people who have HIV. Other studies enroll people who do not have HIV.

Frequently asked questions about HIV cure research

Below are some of the most frequently asked questions by patients to their treatment providers. These are also questions often raised by community members during discussions related to HIV cure.

The first step is to talk to your doctor or health care team and see whether there are any studies ongoing at your centre or in the city where you live. Most cure studies take place in the United States, but some of the larger centres in Canada (Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto, Vancouver) may also have such studies currently or planned for the future. Even if you do not live in a city where a study is being conducted, depending on how far away you live, there may be options to travel to the site where the study is occurring or participate remotely. When you find a study you are interested in learning more about, talk to the study team about what it involves. Typically, the first step is to talk to the study coordinator to learn about the study, the protocol, and whether you are eligible.

The first step is to talk to your doctor or health care team and see whether there are any studies ongoing at your centre or in the city where you live. Most cure studies take place in the United States, but some of the larger centres in Canada (Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto, Vancouver) may also have such studies currently or planned for the future. Even if you do not live in a city where a study is being conducted, depending on how far away you live, there may be options to travel to the site where the study is occurring or participate remotely. When you find a study you are interested in learning more about, talk to the study team about what it involves. Typically, the first step is to talk to the study coordinator to learn about the study, the protocol, and whether you are eligible.

Similarly, there may be risks and side effects associated with the specific therapies being studied. A person has to be aware of the risks and willing to assume these risks to participate in a study. Understanding these risks is a very important part of the consent process, and participants can withdraw from a study at any time. Furthermore, since most HIV reservoir is located within the gut, many cure studies will have invasive procedures such as leukapheresis to extract white blood cells or colonoscopy with gut biopsies. The number and nature of the procedures may impact a person’s willingness to participate. There are other practical considerations as well: If a person works during regular office hours, missing work regularly to attend study visits may not be feasible. People who are able to become pregnant may not meet the criteria for study participation unless they are willing to be on birth control for the duration of the study.

This depends on the nature of the intervention and the data that researchers are collecting (eg. lab work, scans, interviews). Often there will be visits weekly for a period of time and then every 2 weeks. Visits often take at least 2–3 hours. Eventually, this schedule may decline to once a month.

The first step is to talk to your doctor or health care team and see whether there are any studies ongoing at your centre or in the city where you live. Most cure studies take place in the United States, but some of the larger centres in Canada (Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto, Vancouver) may also have such studies currently or planned for the future. Even if you do not live in a city where a study is being conducted, depending on how far away you live, there may be options to travel to the site where the study is occurring or participate remotely. When you find a study you are interested in learning more about, talk to the study team about what it involves. Typically, the first step is to talk to the study coordinator to learn about the study, the protocol, and whether you are eligible.

Most importantly, an intervention should be safe and well-tolerated by participants. In order to determine if it has been effective as a strategy for cure or remission, participants should not experience a viral load rebound when ART is stopped, or the viral load should be at a very low level, for a period of time (for example, two years after stopping ART). For a functional cure, the amount of HIV left in the body must be low enough that it doesn’t impact a person’s health and is not transmittable to others in the absence of ART.

Key Clinical Trials Resources

Community-preferred language to describe cases of HIV cure and control (AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition)

To keep updated with the most recent clinical trials, you can search for specific trials in public databases such as:

- ClinicalTrials.gov: www.clinicaltrials.gov

- WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform: www.who.int/ictrp/en

- European Union Clinical Trials Register: www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu

Find a Study

CTN+ supports clinical trials of the highest scientific standards. Each trial has been approved by national peer review panels.

Latest / Feature Studies:

Browse All StudiesOr Use the Filters

Our People

CTN+ Researchers are the backbone of the Network through generating ideas, collaborating on new initiatives, conducting research, and sharing their knowledge.

Explore Our NetworkJoin the CTN+

Interested in joining the CTN+? We’re always on the lookout for new members to answer the most pressing research questions of today, while anticipating the questions of tomorrow.

Learn More